Family Emergency Communication Plan [FREE DOWNLOAD – Family Emergency Communication Field Operations Card]

Amateur Radio, Emergency Communication, Family, Morale, Survival

You’ve stocked your long-term food storage. The kids can find the emergency meeting place in the dark. Everyone in the family has been trained in basic first aid. The generator has plenty of fuel and the bug-out bags and vehicle are well outfitted just in case you need to get out of Dodge. Then it finally happens, the widespread grid failure that you’ve prepared for throws your town into chaos. It’s time to put all of those best-laid plans to work. But mom and dad are at work, the kids are at friends on the other side of town, and the grandparents are out for a bike ride in the local state park. What is your medium to long-distance family emergency communication plan?

If you’ve planned for this scenario, then you’ve probably arranged a rallying point for everyone to meet, if they’re not together when the “bad day” hits. Unfortunately, today’s mobile society doesn’t make it easy to get to a safe place during a social collapse. With today’s modern travel conveniences it’s easy to be separated from even immediate family members by tens of miles in normal day-to-day lives. But grid failure or collapsed transportation infrastructure or civil unrest will probably render those same modern conveniences useless. Or a flash flood, tornado, or riot may make our pre-planned “landing zone” too hot for “extraction.” How can we quickly, reliably, and securely let everyone involved know that the gathering plan has changed? How do we warn-off our loved ones from traveling back into danger?

With a Family Emergency Communication Plan that you’ll learn to draft and implement here.

Reliable medium to long-distance communication requires two things: electronic devices such as phones, internet devices, or radios; and a communication plan to use them. In the chaos that follows a wide-spread disaster or grid failure a simple and actionable family emergency communication plan will be the difference between your family’s joyous reunion or the unthinkable.

The primary role of our ham radio team in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria was to help families reconnect. Ham radio operators were embedded with Red Cross Reunification teams to help them communicate across the island and the mainland U.S. Reuniting families is a priority for disaster response organizations such as The Red Cross and The Salvation Army. Why? Because they’ve learned that the value of family support in a crisis can’t be overstated but very few people have a plan to make contact after a disaster.

A Family Emergency Communication Plan Should Be Transferable

Sharing valuable information can’t be limited to a particular way of communication. We need to be able to say what needs to be said regardless of what we used to say it. This means that our family communications plan must work with a wide range of devices or tools. It can’t matter whether we use cell phones, morse code, pony express, or smoke signals. A transferable communication plan increases the chance for success; it allows us to choose the best tool available. And the tool that we have is always better than the tool that we don’t have.

I’ve seen this plan work with internet devices, fax machines, radios, and even American sign language.

A Family Emergency Communication Plan

-Background-

In 1906 the first International Radiotelegraph Convention (IRC) adopted the international standards for use on frequency 500 kHz.Those standards went into effect in 1908. The standards were expanded to 24-hour monitoring with the Radio Act of 1912 after the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Then 500 kHz remained the primary distress frequency until the end of the 20th century. Establishing and following these standards saved countless lives at sea.

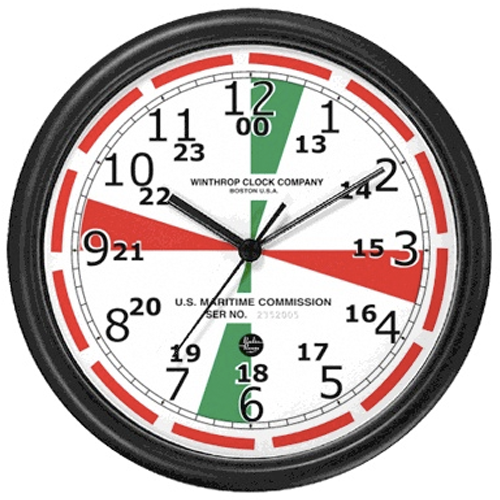

Twice each hour, all stations operating on 500 kHz observed a strictly enforced three-minute silent period, which started at 15 and 45 minutes past the hour. Ship and maritime shore radio rooms were equipped with a clock similar to the one pictured above. The red portions indicate the silent period on 500 kHz and the green ones indicate a similar silence period for 2.182 kHz. All coastal and ship stations monitored the frequency during the silence period. In addition, large ocean vessels monitored 500 kHz 24/7/365 with either a licensed operator on-duty or with automated alarm equipment.

The following is a report by Jeffrey Herman in which he recounts his experience as a radio operator at the USCG station in Honolulu, HI.

The first duty of an operator coming on watch was to check his clock against WWV1 per ITU2 regulations. Certain operations on 500 kHz have to be timed down to the second. In the log it was recorded as:

OBTAINED WWVH TIME TICK – CLOCK CORRECT…2500kHz….0900Z

Because of the steady stream of signals on 500 kHz, a weak station sending a distress message might not be heard. At one time, calls AND traffic were passed on 500 kHz. There was no shifting to working frequencies to pass messages. Thus, silent periods (SP) were created. These consisted of two three-minute intervals in which no one transmits worldwide. Volume controls are turned up; ears are pressed to the speaker grill; one’s breath is held, from minute :15 to minute :18 and again from minute :45 to minute :48. Even if traffic is being passed on working frequencies, it too would stop…at which point I and my listening audience would shift back up to 500 kHz for that particular 3-minute interval.

Pity the station whose clock is off or who forgets the SP, for a half dozen stations might jump on him:

Ship 1: VLA VLA VLA DE 3FWR 3FWR K

Ship 2: QRT SP SP

Ship 1: SRI

Ship 2: SP

Ship 1: OK SRI

Ship 1: SP SP

(Meaning: The ship 3FWR calls the shore station VLA – someone breaks in to tell him to stop transmitting. He responds with ‘sorry’ and is still scolded. Says he’s sorry a second time and is scolded again.) Someone, somewhere in the Pacific was more direct and to the point:

Ship 1: JNKB JNKB DE FHWN FHWN

Ship 2: SHUT UP SP

The last 15 seconds of an SP were set aside for safety and urgent preliminary transmissions.

From the lowest to the highest priority, the following types of broadcasts existed:

CQ – Meaning ‘Hello All Ships and Stations’ sent in a 3X3 format :

CQ CQ CQ DE FUM FUM FUM WX AND TFC LIST QSW 430 AR

Here, the shore station FUM, French Navy Tahiti, makes an announcement that he’ll be sending the weather and his traffic list on 430 kHz. The CQ is the most common broadcast announcement. One CQ will go out every few minutes.

TTT – This is the prosign for a safety broadcast: storm warnings, navigation hazards, or anything involving the safety of shipping:

TTT TTT TTT CQ DE ZLW ZLW ZLW CYCLONE WARNING NR 38 QSW 475 UP

Each T* is sent longer than usual in order to provide a very distinctive sound. During the last 15 seconds of a silent period, a half dozen TTT’s would be going out. In particular, the shore stations running around the perimeter of Australia would send the same TTT, one station following the previous station. Everyone in the Pacific wanted to be the first one out with their TTT announcement instead of waiting for a station 1000 miles away to finish, so many times they’d all go out at once. What a mess!

(*T in Morse code is a single dash.)

XXX – This prosign is indicative of an urgent broadcast where shipping and lives might be in danger (the commanding officer might order the auto alarm sent prior to the preliminary announcement on 500 kHz):

XXX XXX XXX CQ DE NMO NMO NMO HURRICANE WARNING QSW 440 AR

Again, each X is drawn out so as to provide a very distinctive sound. This, as with the TTT announcements, went out during the last 15 seconds of a silent period. Those sending a TTT were supposed to give way to an XXX. Remember, everyone is working duplex3 or full QSK4 – you MUST be able to hear anyone sending under you.

SOS – The darkest hour of an ops (radio) career is when the captain of the ship enters the radio shack, hands the op a piece of paper, and says ‘Send the SOS – here’s our position’. International procedures dictate *every* step that the operator will then take after being alerted by the auto alarm.

Twelve 4-second dashes, each dash followed by a one-second pause, [were transmitted] sent [by the ship in distress]…regulations demand that every ship carry an auto alarm decoding receiver… [which would] only respond to auto alarm’s sent in [this manner].

What you would hear on your receiver, with your BFO on, would be several tones, or harmonics – very musical and an attention-getter… [which] sounds like someone sending [Mores] code on a piano keyboard by pressing a half dozen keys at once!

The auto alarm activated the decoder aboard every ship within receiving distance after four correctly sent dashes are [sic] received. The decoders are designed to be a bit forgiving concerning the timing of the auto alarm dash. They will accept, as a valid dash, a dash of between 3.5 seconds and 6 seconds in length – just in case the sending op is nervous. As mentioned, only four correct dashes are needed, but just to be sure, [regulations] demand that twelve be sent. Once the auto alarm decoder receives four dashes, its latching relay closes activating lights and bells in the radio room, the radio officer’s stateroom, and up on the bridge.

The op in distress now must wait two minutes if possible. If his feet are getting wet, then he skips this step. Off duty operators aboard other ships that have received the auto alarm, must proceed to their radio rooms. 500 kHz is now in a continuous silent period until the controlling station sends:

CQ CQ CQ DE QUM 500 kHz VA

Note that QUM means that distress traffic has ended – resume normal traffic. The controlling station is the distressed vessel. He can and does give control to the first responding shore station. If I was the first shore station to respond, then NMO (call sign for the US Coast Guard in Honolulu) would be the controlling station.

Pity ANY ship or shore station that transmits normal traffic during distress. That station would hear…

QRT QRT QRT SOS 500 (sent by dozens of stations)

[Meaning: STOP TRANSMITTING, STOP TRANSMITTING, STOP TRANSMITTING!!! There is an SOS on this frequency (500 kHz.)]

All traffic pertaining to the distress will be sent on 500 kHz. Those not in a position to assist will move to [another frequency] while 500 kHz is in distress use. Here is a typical distress broadcast sent at no more than 16 words per minute [per regulation]:

SOS SOS SOS CQ DE 5TER 5TER 5TER BT SOS 281751Z MV PANAMA TRADER TAKING ON WATER ENGINE ROOM FLOODED POSN 13.73N 152.55W 13.73N 152.55W NEED IMMEDIATE ASSISTANCE AR MASTER SOS

[CQ means “calling any station”; DE means “this is”; 5TER is the call sign of the ship in trouble. Translated into English this message says, “EMERGENCY, EMERGENCY, EMERGENCY this is ship 5TER 5TER 5TER BREAK EMERGENCY at time 5:51 pm ZULU time today motorized vessel Panama Trader is taking on water and the engine room is flooded. We’re at 13.73N 152.55W; we’re at 13.73N 152.55W. We need immediate assistance OUT EMERGENCY.]

This broadcast would be followed by a 10-second long dash to aid receiving stations in getting a bearing to 5TER’s position.

Then would come the acknowledgments:

SOS 5TER 5TER DE NMO NMO NMO R R R SOS

SOS 5TER DE KFS KFS KFS R R R SOS

SOS 5TER 5TER 5TER DE JNA JNA JNA R R R SOS

SOS 5TER 5TER 5TER DE WNPH WNPH WNPH R R R SOS WE ARE IN POSN 11.81N 151.32W

CHANGING CSE TO UR POSN WILL GET ETA K

SOS WNPH DE 5TER R TU HERE IS MORE INFO …..

The first thing you’ll notice is that all transmissions must start with SOS (ITU regulations). What happened here is that three shore stations acknowledged the distress broadcast.

(You can read more about Mr. Herman’s experiences as a U.S. Coast Guard radioman at http://jproc.ca/radiostor/cw500pt1.html)

The part of Mr. Herman’s account for us to take away is the listening process. A ship in distress could call at any time, but their signal might be covered up by routine communication. The distressed station knew that for three minutes every hour every maritime two-way radio station in the world would be listening. And every single ship at sea knew that every other maritime station would be listening and paying attention at those times. If you called for help, someone would hear you.

Adapting the Maritime Regulations for 500 kHz into a Family Emergency Communication Plan

This approach adapts well to various modes of communication. In fact, many of us already use it.

Imagine your extended family is at a large amusement park as part of a family reunion. At some point, the adventurous family members will want to ride every roller coaster at least twice, while the more timid among you prefer the teacup ride. Then there are always those two or three that just want to sit and eat funnel cakes. Of course, the lines at the roller coasters are much longer than at the teacups and the funnel cake kiosk is on the other side of the park. So you decide to split up. Before you do you make sure that each group has a cell phone and you exchange phone numbers.

Then you establish a schedule. At the top and bottom of every hour, everyone will send a text indicating their location. Or you decide that everyone will check-in by calling at the top of the hour. Of course, anyone can call or text at any time, but we humans are notorious for distraction both to and away from our phones. We all have that person in our life that doesn’t answer phone calls or texts until hours later, excusing it with, “Oh, my phone was on silent,” or some other lame excuse. Pre-establishing a check-in schedule empties this excuse of its power, but the regular check-in is also a back-up to missed check-ins. One of the other groups may have seen the “AWOL” group and can provide a general location report at the check-in time if needed.

This strategy can be applied at an even more basic level. In many couples, one of the two is an introvert while the other is an extravert. In our family, my wife is the extravert, and me not so much. Large gatherings wear me out, but they give my wife energy. Unfortunately, being an introvert I’m also uncomfortable with being the reason we’re the first to leave the party; I don’t want to hurt the host’s feelings and eventually feel trapped between the two. Thankfully, my wife is sensitive to my plight and, being an extravert, is adept at navigating the early farewell without damaging relationships. (I outkicked my coverage when I married her!)

Our unspoken plan is for her to periodically check-in with me to make sure that I’m not “sinking” in awkward small talk that I can’t extricate myself from. It might be as simple as her looking across a crowded room every 20-30 minutes to see if I’m enjoying myself. Other times it’s pre-planned for her to saunter over and interrupt an interminable story about some lady’s cats. Either way, it’s a great solace for this introvert to know that rescue from my deserted island is never more than a few minutes away.

How to Use the Ham Radio Wilderness Protocol as Your Family Emergency Communication Plan

Of course, what I’ve described above is a far cry from a disaster or other worst-case scenario. When a really “bad day” happens cell phones are going to be useless, either from infrastructure failure or from circuits being overwhelmed.

And the “party strategy” isn’t actionable because it depends on line-of-sight communication. Medium or long-distance contacts are best accomplished through radio wave technology.

As I said earlier, the strategy discussed here can be applied to many situations and implemented with a wide variety of tools. If voice cell phone coverage is available, that’s your best bet for two-way comms. If voice by cell phone won’t get through, try texting because it’s store-and-forward. It might not go through right away, but it might eventually make it. But texting breaks down in that it is cumbersome and doesn’t convey emotion well.

This is where radio communication reigns supreme. Two-way radio can instantly transmit valuable information to multiple people in multiple locations literally at the speed of light. Depending on the type of radio used the distance covered can be from less than one mile to thousands of miles, instantly.

Regardless of which radio technology is available, we use the ham radio Wilderness Emergency Communications Protocol as the basis for our family emergency communication plan.

First introduced by William Alsup in the 1994 issue of QST the Wilderness VHF FM Protocol is loosely patterned after the procedures for maritime 500 kHz. It has proven effective for use with handheld ham radios in the backcountry. Since its inception it has been adapted by preppers, survivalists, outdoors enthusiasts, hunters, and others with a multitude of radios including CB, FRS, GMRS, and MURS radios. I’ll describe the protocol used by ham radio operators along with tips for adapting it to other radio services.

Ham radio operators implementing the protocol monitor the “calling frequencies” of ham radio whenever possible, specifically those frequencies above 50 MHz. The most commonly used calling frequency is 146.520 MHz on the 2-meter wavelength. Much like the procedures for the 500 kHz this protocol sets aside specific times for safety checks. These safety checks occur for 5 minutes at the top of the hour at 10 AM, 1 PM, and 4 PM (all local times). Stations in proximity to the wilderness area are encouraged to also monitor the calling frequency for the first 5 minutes of each hour. This is a well-thought-out plan, but it needs some tweaking to be used in a bug-out or bug-home situation.

First, the whole point of bugging-out or getting to a rallying point is to get to or maintain safety. Operational security (OPSEC) is paramount. We don’t want to announce what our plans are to whoever might be listening. The first and most effective step that we can take in our family communication plan is to avoid frequencies that are commonly used. Avoid the calling frequencies because of their popularity. The more obscure the frequency, the better. But remember to stay within the appropriate band-plan privileges for your amateur class license and mode of transmission. Our family uses an undisclosed FM simplex frequency in the 2-meter band. We use 2 meters because that holds the best chance for success up to tens of miles.

Second, our family communication plan calls for safety checks every thirty minutes at the fifteens (15 minutes after the hour and 15 minutes before the top). This is much more often than the wilderness protocol. Waiting three hours between calls is too long in a worst-case scenario. The average person in reasonably good health can walk 2-3 miles per hour. It’s likely that our loved ones will be scattered within a radius of 20 miles when the “lights go out,” and a 5-watt walkie-talkie can communicate across 5-10 miles. This means communication might be established within the first 20 to 40 minutes of the crisis.

Third, we employ the Long Tone Zero (LiTZ) protocol. LiTZ is helpful in getting a monitoring station’s attention or for reporting “ALL OK” without needing to speak into a microphone. (Yes, not IDing is technically a violation of FCC regulations, but that’s the least of my worries if I need to keep my voice down to keep from drawing attention in my immediate vicinity.)

To implement a LiTZ hold down the “0” key on your radio’s DTMF (dual-tone multi-frequency) keypad for at least 3 seconds. Any receiving stations respond in the same way. If we want to confirm that all is well, then the first person replies with 3 one second LiTZ transmissions. If all is OK, then a reply of 4 LiTZ is sent. (In our family, three hand squeezes is a way to inconspicuously say “I love you.” A reply of 4 squeezes is “I love you, too.”) If all is not well, then no reply is sent and everyone changes the rallying point to a predetermined secondary location.

We’ve adapted the family emergency communication plan for even a long-distance bug-out scenario. My adult daughter lives about 600 miles from us. Our long-term bug-out location is farther beyond that. Our long-distance bug-out plan is to gather our loved ones nearby, then head toward that undisclosed location, picking her up along the way. I’ve provided her with a walkie-talkie that is pre-programmed with the proper frequencies. If a regional disaster strikes she knows to turn on the radio and monitor the predetermined frequency for 5 minutes every 30 minutes on the 15s. Yes, her walkie-talkie isn’t capable of transmitting 600 miles, but under favorable conditions, my base and mobile stations might just have enough “oomph” for her to copy our status messages while we’re on our way.

(By the way, this approach can be applied to much longer distances on high frequencies. I suggest establishing both a 40 meter and 20-meter calling frequency. The closer to the band edges, the better, particularly if everyone involved has Amateur Extra privileges.)

If you’re looking to buy a ham radio for your family emergency communication plan? Please check out my post “The Best Ham Radio for Preppers” on the Willow Haven Outdoors website. There I describe the Yaesu FT-60 which has some enhanced emergency communication features.

The Family Emergency Communication Plan for Non-ham Radios

This family emergency communication plan can be used with many other radios, too: CBs, GMRS, and FRS (the cheap ones you can buy at big box stores), even the little Disney princess radios that you bought for your daughter ten Christmases ago.

These radios don’t tune to frequencies in the same way that ham radios do. They’re what is called “channelized.” CB radios have 40 channels. GMRS radios have 30 channels 22 of which are shared with FRS. GMRS and FRS operators can communicate with each other on these shared frequencies. MURS radios have 5 channels. Just designate a channel that is common to all of your radios as your family emergency communication plan calling channel. Then apply the strategy described above. I suggest choosing channels toward the upper end of the range. The lower channels will probably be the first to be used by other people in an emergency. Definitely avoid channels 1, 9, and 19 on CB radios. They’ll be good for gathering information, but not for two-way communication during a disaster. (CB channel 9 is designated for emergency assistance, but that’s intended for one person in distress, not TEOTWAWKI.)

Marine radios can work with this strategy, too. But they tend to be more expensive and their channels will probably be crowded in a crisis.

Many non-ham radios also have a way to generate audible tones much like holding down the “0” key in LiTZ. There are too many variations to address them all here, so do some experimentation.

Also, there is a PL-tone feature on most radios. PL-tones can provide rudimentary privacy, but their use is outside the scope of this post.

Please keep in mind that all of the non-ham radio options are limited in versatility and transmission distance compared to ham radios. Even 50-watt versions of GMRS radios are limited in frequency agility. The best communication advice that I can give you is to get your ham radio license. Even young ones of 7 or 8 years old can pass the test. I guarantee that you’ll earn your license with the Ham Cram course at outdoorcore.com.

The Family Emergency Communication

Field Operation Card

There you have it. It’s not that complicated and is both transferable and scalable. Many prepper communities have adopted a version of this strategy. For long-term radio communication, many people in the prepper community use the 3-3-3 Radio Plan which builds on the Survival Rule of Threes. I encourage you to take a look at some of their plans and the frequencies that they use. Look to see if any of them are near you and connect with them as you’re comfortable. It helps to know that there are like-minded people that are out there listening during a crisis.

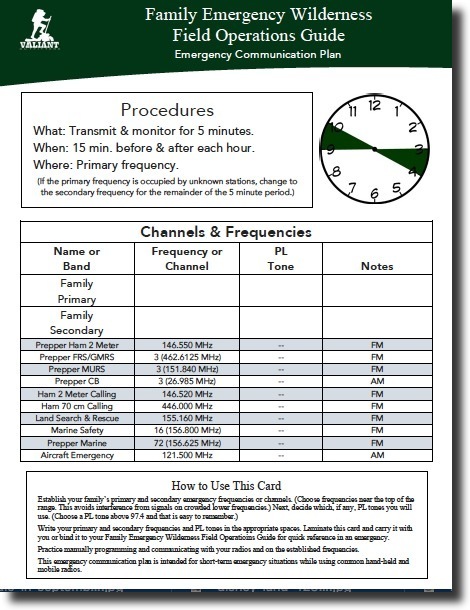

And be sure to download the free pocket-sized Family Emergency Communication Field Operation Card. It lists all of the ham VHF calling frequencies, a chart for listing your own frequencies and safety-check times, and much of the information in the Emergency Radio Frequencies Every Prepared Family Knows blog post. Download it, print it, add your information, and laminate it so that all of your family can have it in their everyday carry.

More field operation cards that cover everything from foraging for food to shelter setups to how to light a fire will be available in the future. They’re bindable so that you can add them to our pocket-sized Family Emergency Field Operations Guide.

Survival is more than just staying alive.

Click here to read a great post by Greywolf Survival about How to Communicate When the World Goes Silent.